Fashion’s Silent Rebels: How Disability and Difference Are Reshaping the Industry

On May 17, 2025, the fashion world witnessed a seismic shift: Every Bodies, an inclusive runway event organized by PIH (Pour l’Inclusion par l’Habillage). This was not a showcase of standardized silhouettes or sanitized perfection, but a celebration of unapologetic diversity — wheelchairs, prosthetics, atypical movements, unique postures. The body, in all its realities, reclaimed the stage. It became narrative, protest, presence. This was not just a show; it was a manifesto.

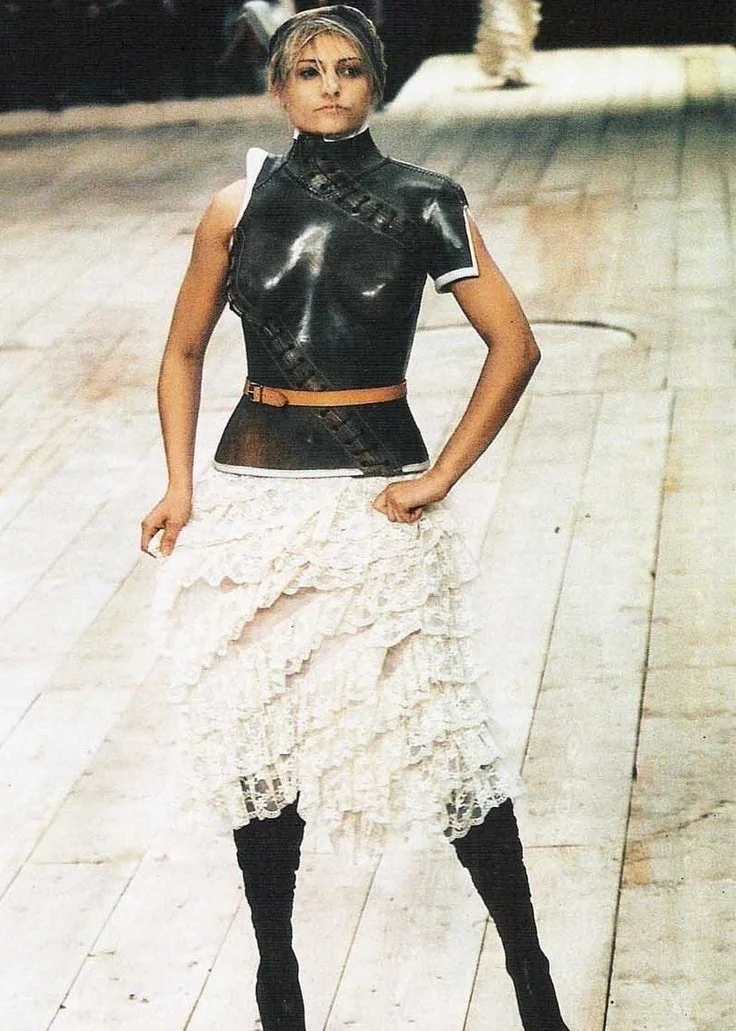

For centuries, people with disabilities were relegated to care and hospital settings, almost entirely excluded from the realms of fashion and aesthetic representation. The first real discussions around equality only emerged in 1981, when the United Nations declared the International Year of Persons with Disabilities. Yet it took until 1999 for a model with a disability — Aimee Mullins — to walk a major runway, for Alexander McQueen during London Fashion Week, wearing custom-carved wooden prosthetics.

While symbolic, this historic moment did not trigger the structural change the industry needed.

Over time, however, small movements have emerged. From Tommy Hilfiger's Adaptive line, designed after witnessing his daughter's struggles with buttons and laces, to the Barbie Fashionistas collection featuring dolls with visible disabilities, a new narrative has started to form. According to the World Health Organization, over 1.3 billion people — 15 percent of the global population — live with a disability. And yet, Dazed reports that only 0.02 percent of fashion campaigns feature disabled models.

Trailblazers like Aaron Rose Philip, the first Black, trans, wheelchair-using model signed to a major agency, are shifting the paradigm. Philip has walked in multiple shows for Collina Strada, a brand praised for its consistent casting of models from disabled, transgender, and non-binary communities. In her words, “[Collina Strada has] always been the ones to understand me and see me for my actual talents as a dedicated model.” But this level of understanding remains rare. Many other castings still fall into tokenism, treating disability as a seasonal trend rather than a creative and structural inclusion.

Fashion’s true power lies in its ability to shape perception. As Essence and Neighbourhood Mag have pointed out, disability is often left out of the diversity conversation — an afterthought to race, gender, or size. Laura Winson, founder of Zebedee Talent, calls it “the last taboo.” Inclusive campaigns like British Vogue’s cover featuring Ellie Goldstein and Selma Blair mark progress, but they are still exceptions in a landscape where disabled representation remains fragile.

The shift we need is not just visual, but systemic. From runway to backstage, from design to retail, inclusion must be embedded. Adaptive fashion, once niche, is gaining traction thanks to initiatives like Open Style Lab, founded at MIT, and brands such as IZ Adaptive, Abilitee, and So Yes, which innovate with magnetic closures, sensory-friendly fabrics, and seated cuts for people with disabilities. These are not concessions — they are aesthetic innovations.

But visibility is not enough. As April Lockhart, disabled model and influencer, notes, “More times than not, I’m the only disabled influencer at events or represented in campaigns.” While social media has allowed her to control her image and connect with a broader community, she emphasizes how far the industry still has to go. “There isn’t a roadmap to follow or someone to look up to,” she says. And when inclusion is rare, it puts the burden of representation on the few who break through.

For April and others, platforms like Instagram and TikTok have become critical spaces of empowerment — places where disabled creatives no longer wait for approval, but instead claim visibility and build community. Her collaborations with brands like Anthropologie, or her presence at the White House, illustrate what happens when the industry listens — and invests.

Yet these examples are still isolated. Brands like Victoria’s Secret, once a symbol of narrow ideals, only recently featured Sofia Jirau, a model with Down syndrome, and Miriam Blanco, who has a physical disability, in their Love Cloud Collection. The move came after years of criticism and felt, for many, like a reactive pivot rather than a long-term vision.

Projects like Runway of Dreams, Models of Diversity, and London Represents have created more inclusive fashion platforms, often independently from the mainstream. But the goal is not to remain a niche. As many disabled voices remind us, inclusion should not rely on special projects. It should be the norm.

Not all disabilities are visible. Nina Marker, an autistic model, has walked for luxury houses like Dior, Givenchy, and Valentino. While this proves progress is possible, the continued absence of visibly disabled models on luxury runways reflects how deep the stigma still runs.

When disabled models appear, their presence disrupts more than aesthetics. It reshapes who fashion is for, who it reflects, and who it invites to dream. What Every Bodies affirmed is that inclusion is no longer optional — it is essential. It is not about checking a box. It is about shifting the foundation.

The future of fashion lies not in uniformity, but in multiplicity.

Not in perfection, but in presence.

Inclusion is not a trend. It is a creative, ethical, and cultural imperative.